A resident of New Bern, NC, may in fact have a new boat

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

On Wednesday, after flying to the Cherry Point Marine Corps Air Station in hurricane-hit North Carolina, the President drove a half-hour up the Neuse River to the town of New Bern, where among other things he spoke briefly with a homeowner who had discovered a sailboat leaning against his deck (from the day's pool report, emphasis ours):

Trump gazed at the yacht, saying, Is this your boat? The owner said no. Trump turned and replied with smile, At least you got a nice boat out of the deal... I think it's incredible what were seeing, the president added. This boat just came here. They don't know whose boat that is, he said. What's the law? Maybe it becomes theirs.

The president, the homeowner and the yacht led the day's coverage, mostly as an example of the offhand way Mr Trump handles interactions in public. Alphaville admits to a preoccupation with this story, having spent part of our childhood sailing up and down that very stretch of the Neuse River. But having looked into the laws around abandoned vessels in North Carolina, we are happy to report the following: The President may in fact be correct. It's entirely possible — though not likely — that a homeowner in New Bern ends up owning a boat.

Most private yachts are built out of fiberglass, which ensures that they 1) are cheap to make and buy and 2) will never rot. Junk fiberglass hulls are increasingly plentiful, hard to sell, expensive to scrap and therefore increasingly abandoned. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Marine Debris Program is responsible for worrying about the problem in the U.S., but everyone and no one is responsible for paying for it. For coastal states, derelict boats show up exactly when there's the least amount of money to deal with them: after a hurricane, and during a recession. But unlike states like Washington or Maryland, North Carolina does not have specific laws for derelict private yachts, or dedicated funding to pay for removal.

It's a knotty problem, in essence unchanged for the last thousand years. Abandoned or sunken vessels and their cargo have value. But salvage — recovery — is expensive. So every marine salvage law since the Maritime Ordinances of Trani in 1063 has had to balance the rights of the owner against the costs incurred by the salvor and the state, which needs to get abandoned vessels out of marine channels, where they obstruct passage and therefore commerce.

Alphaville trusts that its readers understand the importance of passage and commerce.

So in New Bern, here are the five questions we need to answer:

What is the current value of the boat?

Who is the nominal owner?

What is the cost of salvage?

Does the owner wish to pay the cost of salvage?

If not, who will pay for salvage?

If the owner doesn't want the boat and no one will pay for salvage, it becomes abandoned private property on someone's lawn. Which means: it becomes the homeowner's problem, and the homeowner's boat.

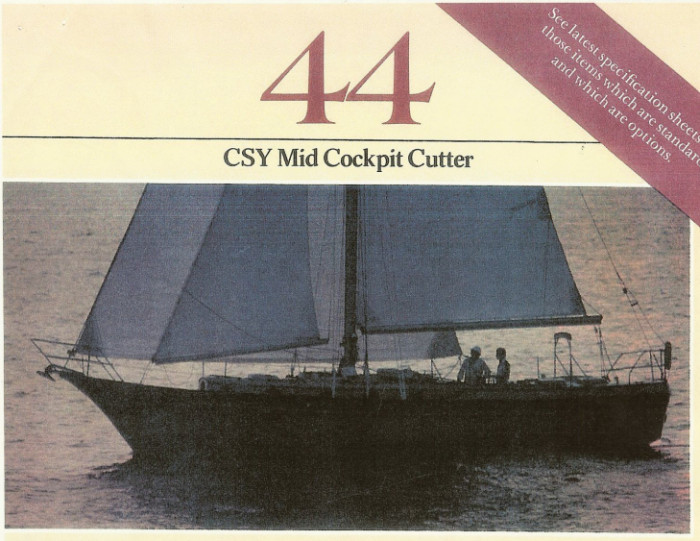

The boat is probably — but not definitely — still worth $80k-$100k

The President is right: it's a nice boat. Alphaville spent a pleasant half-hour on Thursday browsing center-cockpit cruising cutters, and has determined that it's a CSY 44, one of Cruising World magazine's 40 best boats of all time. They list between $80k and $110k. Before the hurricane, this particular boat likely floated on the high end of that range. The fiberglass is clean and bright. The teak has been recently oiled. On the stern sit stainless-steel dingy davits with solar panels. These are expensive and difficult to install, and suggest that the rest of the boat is outfitted with expensive gear for long-range cruising.

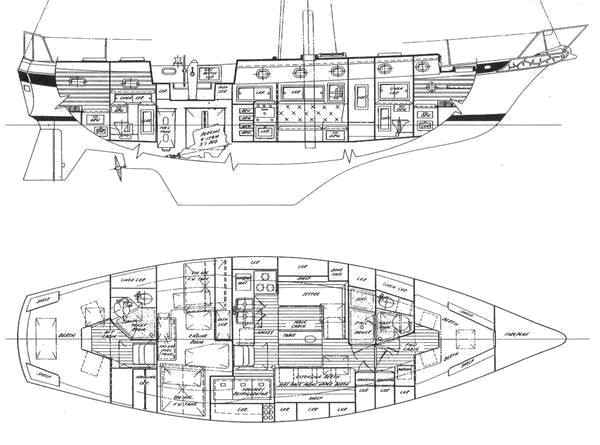

The boat likely retains much of its value even now. CSY 44s were designed for the charter trade in the Caribbean — they were built strong, to be frequently run aground by idiots. The hull is an inch and a half thick, laid up with 14 layers of fiberglass and reinforced to LLoyd's Register's Rules and Regulations. It's unlikely to have a hull breach: sunk boats don't float onto someone's lawn. Boats can suffer expensive damage to rudders and propeller shafts when they take the ground, but the CSY 44 hangs its rudder on a skeg for protection (see above), and tucks its propeller up behind a stub keel.

It's a nice boat. Here's a glam shot from the '80s .

However: it could still be a total loss. A boat like that could still float with three feet of rainwater or even worse saltwater in the cabin, but: electronics, interior carpentry and the diesel engine would be unrecoverable. The boat likely still has most of its value, but we just don't know.

The owner will be easy to find, but salvage will be expensive

It's also likely that the owner can be found, and still wants the boat. The dodger and bimini — canvas shelters over the cockpit that keep out sun and spray - have been removed. So have the roller-furling headsails, which can unroll in a hurricane, ripping the boat away from its mooring.. The owner cares about the boat enough to prep for a hurricane and keep the teak bright. And even if the owner can't find the boat, it came to rest above the water, which means its registration number is visible. The owner is findable.

It is very expensive, however, to remove a 44-boat cruising cutter from someone's porch and get it back in the water. Dry-land salvage requires cranes and slings and flatbeds and many hours of patient engineering. To get a 38-foot sailboat out of the end zone of a high school football field in Coconut Grove, Florida last year cost $20,000. And our CSY 44 is a significantly larger boat.

Only about half the boats in the U.S. are insured. In North Carolina, jet skis must carry $300k of liability cover, because have you ever watched someone operate a jet ski? But Class 3 recreational vessels — our CSY 44 — are under no obligation to carry insurance at all. The boat's owner does seem like a conscientious skipper. But it's entirely possible that our skipper is on the hook for the entire cost of salvage.

In which case:

If the boat has filled with rainwater or seawater, greatly reducing its value, and

If the skipper doesn't carry insurance to pay for the salvage, and

If the salvage operation turns out to be particularly expensive, then

The boat's owner walks quietly away and takes up windsurfing, because:

North Carolina, unlike Florida, does not oblige boat owners to pay for salvage, and

A North Carolina precedent allows a boat owner to abandon ownership simply by appearing to be "without hope of recovery or without intention of returning."

Now the homeowner has a problem. There's a boat on his porch, and no one's coming to get it.

The Army Corps of Engineers, the Coast Guard, FEMA and North Carolina won't pay for salvage

Last year Congress asked the Government Accountability Office to catalogue the long chain of federal and state agencies and laws that govern abandoned and derelict vessels. In a federally maintained waterway, the Army Corps pays to keep the channels clear, but this is only about 75 boats a year. If the vessel is in the water outside a federal waterway and presents a public health hazard — leaking diesel fuel, for example — the Coast Guard will remove it.

If there's been a storm, the Federal Emergency Management Agency may offer a one-time grant, as it did for 242 boats after Hurricane Katrina, and 570 boats after Superstorm Sandy. North Carolina accepts the responsibility to work with federal agencies on abandoned boats, but again has no dedicated fund for the work. A pilot program to pay for boat removal along the Neuse River Basin in the early 2000s was not renewed.

But none of this applies here, because the boat is not in the water. The Environmental Protection Agency pays to remove a small number of boats on dry land every year — 2013 was a notable exception, with 90 vessels after Sandy — but this is mostly about mitigating diesel spills.

If the boat is abandoned, the homeowner pays for salvage

Here's NOAA's summary of North Carolina's abandoned vessel precedents. If he can prove to the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission that someone has in fact abandoned a cared-for and hurricane-prepped CSY 44, he can claim ownership. The state treats an abandoned boat on private land as a civil matter, so legally, the homeowner owns a very long, very heavy derelict car.

So it's completely reasonable for the President to say a nice boat floated, up and wonder whether it belongs to the homeowner now. But if it does, the homeowner has that ancient problem: a boat is leaning against his porch. He can rent it out as an AirBNB, but if he wants to sail it, he still has to pay for salvage, which is still tens of thousands of dollars.

The most likely outcome: The boat's owner is a responsible, careful skipper who values the boat and will pay to put it back in the water.

The second most likely outcome: The homeowner takes possession, but immediately hands the title over to a professional salvor, as payment for having it removed.

The third most likely, but not completely absurd outcome: Like the President said, the homeowner got a nice boat out of the deal.

It is a really nice boat.

Comments